“She just wanted to be somewhere safe, somewhere familiar, where people looked and spoke like her and she could stand to eat the food.” —Midnight Robber by Nalo Hopkinson

Midnight Robber (2000) is about a woman, divided. Raised on the high-tech utopian planet of Touissant, Tan-Tan grows up on a planet populated by the descendants of a Caribbean diaspora, where all labor is performed by an all-seeing AI. But when she is exiled to Touissant’s parallel universe twin planet, the no-tech New Half-Way Tree, with her sexually abusive father, she becomes divided between good and evil Tan-Tans. To make herself and New Half-Way Tree whole, she adopts the persona of the legendary Robber Queen and becomes a legend herself. It is a wondrous blend of science fictional tropes and Caribbean mythology written in a Caribbean vernacular which vividly recalls the history of slavery and imperialism that shaped Touissant and its people, published at a time when diverse voices and perspectives within science fiction were blossoming.

Science fiction has long been dominated by white, Western perspectives. Verne’s tech-forward adventures and Wells’ sociological allegories established two distinctive styles, but still centered on white imperialism and class struggle. Subsequent futures depicted in Verne-like pulp and Golden Age stories, where lone white heroes conquered evil powers or alien planets, mirrored colonialist history and the subjugation of non-white races. The civil rights era saw the incorporation of more Wellsian sociological concerns, and an increase in the number of non-white faces in the future, but they were often tokens—parts of a dominant white monoculture. Important figures that presaged modern diversity included Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols. Nichols was the first black woman to play a non-servant character on TV; though her glorified secretary role frustrated Nichols, her presence was a political act, showing there was space for black people in the future.

Another key figure was the musician and poet Sun Ra, who laid the aesthetic foundation for what would become known as the Afrofuturist movement (the term coined by Mark Dery in a 1994 essay), which showed pride in black history and imagined the future through a black cultural lens. Within science fiction, the foundational work of Samuel Delany and Octavia Butler painted realistic futures in which the histories and cultural differences of people of color had a place. Finally, an important modern figure in the decentralization of the dominant Western perspective is Nalo Hopkinson.

A similarly long-standing paradigm lies at the heart of biology, extending back to Darwin’s theoretical and Mendel’s practical frameworks for the evolution of genetic traits via natural selection. Our natures weren’t determined by experience, as Lamarck posited, but by genes. Therefore, genes determine our reproductive fitness, and if we can understand genes, we might take our futures into our own hands to better treat disease and ease human suffering. This theory was tragically over-applied, even by Darwin, who in Descent of Man (1871) conflated culture with biology, assuming the West’s conquest of indigenous cultures meant white people were genetically superior. After the Nazis committed genocide in the name of an all-white future, ideas and practices based in eugenics declined, as biological understanding of genes matured. The Central Dogma of the ’60s maintained the idea of a mechanistic meaning of life, as advances in genetic engineering and the age of genomics enabled our greatest understanding yet of how genes and disease work. The last major barrier between us and our transhumanist future therefore involved understanding how genes determine cellular identity, and as we’ll see, key figures in answering that question are stem cells.

***

Hopkinson was born December 20, 1960 in Kingston, Jamaica. Her mother was a library technician and her father wrote, taught, and acted. Growing up, Hopkinson was immersed in the Caribbean literary scene, fed on a steady diet of theater, dance, readings, and visual arts exhibitions. She loved to read—from folklore, to classical literature, to Kurt Vonnegut—and loved science fiction, from Spock and Uhura on Star Trek, to Le Guin, James Tiptree Jr., and Delany. Despite being surrounded by a vibrant writing community, it didn’t occur to her to become a writer herself. “What they were writing was poetry and mimetic fiction,” Hopkinson said, “whereas I was reading science fiction and fantasy. It wasn’t until I was 16 and stumbled upon an anthology of stories written at the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop that I realized there were places where you could be taught how to write fiction.” Growing up, her family moved often, from Jamaica to Guyana to Trinidad and back, but in 1977, they moved to Toronto to get treatment for her father’s chronic kidney disease, and Hopkinson suddenly became a minority, thousands of miles from home.

Development can be described as an orderly alienation. In mammals, zygotes divide and subsets of cells become functionally specialized into, say, neurons or liver cells. Following the discovery of DNA as the genetic material in the 1950s, a question arose: did dividing cells retain all genes from the zygote, or were genes lost as it specialized? British embryologist John Gurdon addressed this question in a series of experiments in the ’60s using frogs. Gurdon transplanted nuclei from varyingly differentiated cells into oocytes stripped of their genetic material to see if a new frog was made. He found the more differentiated a cell was, the lower the chance of success, but the successes confirmed that no genetic material was lost. Meanwhile, Canadian biologists Ernest McCulloch and James Till were transplanting bone marrow to treat irradiated mice when they noticed it caused lumps in the mice’s spleens, and the number of lumps correlated with the cellular dosage. Their lab subsequently demonstrated that each lump was a clonal colony from a single donor cell, and a subset of those cells was self-renewing and could form further colonies of any blood cell type. They had discovered hematopoietic stem cells. In 1981 the first embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from mice were successfully propagated in culture by British biologist Martin Evans, winning him the Nobel Prize in 2007. This breakthrough allowed biologists to alter genes in ESCs, then use Gurdon’s technique to create transgenic mice with that alteration in every cell—creating the first animal models of disease.

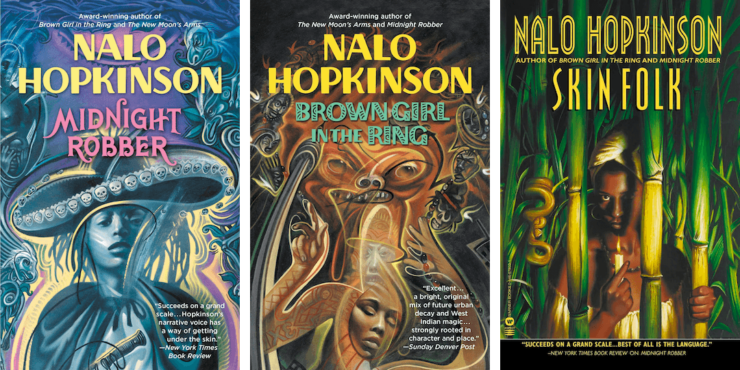

In 1982, one year after Evans’ discovery, Hopkinson graduated with honors from York University. She worked in the arts, as a library clerk, government culture research officer, and grants officer for the Toronto Arts Council, but wouldn’t begin publishing her own fiction until she was 34. “[I had been] politicized by feminist and Caribbean literature into valuing writing that spoke of particular cultural experiences of living under colonialism/patriarchy, and also of writing in one’s own vernacular speech,” Hopkinson said. “In other words, I had models for strong fiction, and I knew intimately the body of work to which I would be responding. Then I discovered that Delany was a black man, which opened up a space for me in SF/F that I hadn’t known I needed.” She sought out more science fiction by black authors and found Butler, Charles Saunders, and Steven Barnes. “Then the famous feminist science fiction author and editor Judy Merril offered an evening course in writing science fiction through a Toronto college,” Hopkinson said. “The course never ran, but it prompted me to write my first adult attempt at a science fiction story. Judy met once with the handful of us she would have accepted into the course and showed us how to run our own writing workshop without her.” Hopkinson’s dream of attending Clarion came true in 1995, with Delany as an instructor. Her early short stories channeled her love of myth and folklore, and her first book, written in Caribbean dialect, married Caribbean myth to the science fictional trappings of black market organ harvesting. Brown Girl in the Ring (1998) follows a young single mother as she’s torn between her ancestral culture and modern life in a post-economic collapse Toronto. It won the Aspect and Locus Awards for Best First Novel, and Hopkinson was awarded the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer.

In 1996, Dolly the Sheep was created using Gurdon’s technique to determine if mammalian cells also could revert to more a more primitive, pluripotent state. Widespread animal cloning attempts soon followed, (something Hopkinson used as a science fictional element in Brown Girl) but it was inefficient, and often produced abnormal animals. Ideas of human cloning captured the public imagination as stem cell research exploded onto the scene. One ready source for human ESC (hESC) materials was from embryos which would otherwise be destroyed following in vitro fertilization (IVF) but the U.S. passed the Dickey-Wicker Amendment prohibited federal funding of research that destroyed such embryos. Nevertheless, in 1998 Wisconsin researcher James Thomson, using private funding, successfully isolated and cultured hESCs. Soon after, researchers around the world figured out how to nudge cells down different lineages, with ideas that transplant rejection and genetic disease would soon become things of the past, sliding neatly into the hole that the failure of genetic engineering techniques had left behind. But another blow to the stem cell research community came in 2001, when President Bush’s stem cell ban limited research in the U.S. to nineteen existing cell lines.

Buy the Book

Trouble the Saints

In the late 1990s, another piece of technology capturing the public imagination was the internet, which promised to bring the world together in unprecedented ways. One such way was through private listservs, the kind used by writer and academic Alondra Nelson to create a space for students and artists to explore Afrofuturist ideas about technology, space, freedom, culture and art with science fiction at the center. “It was wonderful,” Hopkinson said. “It gave me a place to talk and debate with like-minded people about the conjunction of blackness and science fiction without being shouted down by white men or having to teach Racism 101.” Connections create communities, which in turn create movements, and in 1999, Delany’s essay, “Racism and Science Fiction,” prompted a call for more meaningful discussions around race in the SF community. In response, Hopkinson became a co-founder of the Carl Brandon society, which works to increase awareness and representation of people of color in the community.

Hopkinson’s second novel, Midnight Robber, was a breakthrough success and was nominated for Hugo, Nebula, and Tiptree Awards. She would also release Skin Folk (2001), a collection of stories in which mythical figures of West African and Afro-Caribbean culture walk among us, which would win the World Fantasy Award and was selected as one of The New York Times’ Best Books of the Year. Hopkinson also obtained master’s degree in fiction writing (which helped alleviate U.S. border hassles when traveling for speaking engagements) during which she wrote The Salt Roads (2003). “I knew it would take a level of research, focus and concentration I was struggling to maintain,” Hopkinson said. “I figured it would help to have a mentor to coach me through it. That turned out to be James Morrow, and he did so admirably.” Roads is a masterful work of slipstream literary fantasy that follows the lives of women scattered through time, bound together by the salt uniting all black life. It was nominated for a Nebula and won the Gaylactic Spectrum Award. Hopkinson also edited anthologies centering around different cultures and perspectives, including Whispers from the Cotton Tree Root: Caribbean Fabulist Fiction (2000), Mojo: Conjure Stories (2003), and So Long, Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy (2004). She also came out with the award-winning novel The New Moon’s Arms in 2007, in which a peri-menopausal woman in a fictional Caribbean town is confronted by her past and the changes she must make to keep her family in her life.

While the stem cell ban hamstrung hESC work, Gurdon’s research facilitated yet another scientific breakthrough. Researchers began untangling how gene expression changed as stem cells differentiated, and in 2006, Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University reported the successful creation of mouse stem cells from differentiated cells. Using a list of 24 pluripotency-associated genes, Yamanaka systematically tested different gene combinations on terminally differentiated cells. He found four genes—thereafter known as Yamanaka factors—that could turn them into induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and he and Gurdon would share a 2012 Nobel prize. In 2009, President Obama lifted restrictions on hESC research, and the first clinical trial involving products made using stem cells happened that year. The first human trials using hESCs to treat spinal injuries happened in 2014, and the first iPSC clinical trials for blindness began this past December.

Hopkinson, too, encountered complications and delays at points in her career. For years, Hopkinson suffered escalating symptoms from fibromyalgia, a chronic disease that runs in her family, which interfered with her writing, causing Hopkinson and her partner to struggle with poverty and homelessness. But in 2011, Hopkinson applied to become a professor of Creative Writing at the University of California, Riverside. “It seemed in many ways tailor-made for me,” Hopkinson said. “They specifically wanted a science fiction writer (unheard of in North American Creative Writing departments); they wanted someone with expertise working with a diverse range of people; they were willing to hire someone without a PhD, if their publications were sufficient; they were offering the security of tenure.” She got the job, and thanks to a steady paycheck and the benefits of the mild California climate, she got back to writing. Her YA novel, The Chaos (2012), coming-of-age novel Sister Mine (2013), and another short story collection, Falling in Love with Hominids (2015) soon followed. Her recent work includes “House of Whispers” (2018-present), a series in DC Comics’ Sandman Universe, the final collected volume of which is due out this June. Hopkinson also received an honorary doctorate in 2016 from Anglia Ruskin University in the U.K., and was Guest of Honor at 2017 Worldcon, a year in which women and people of color dominated the historically white, male ballot.

While the Yamanaka factors meant that iPSCs became a standard lab technique, iPSCs are not identical to hESCs. Fascinatingly, two of these factors act together to maintain the silencing of large swaths of DNA. Back in the 1980s, researchers discovered that some regions of DNA are modified by small methyl groups, which can be passed down through cell division. Different cell types have different DNA methylation patterns, and their distribution is far from random; they accumulate in the promoter regions just upstream of genes where their on/off switches are, and the greater the number of methyl groups, the lesser the gene’s expression. Furthermore, epigenetic modifications, like methylation, can be laid down by our environments (via diet, or stress) which can also be passed down through generations. Even some diseases, like fibromyalgia, have recently been implicated as such an epigenetic disease. Turns out that the long-standing biological paradigm that rejected Lamarck also missed the bigger picture: Nature is, in fact, intimately informed by nurture and environment.

In the past 150 years, we have seen ideas of community grow and expand as the world became more connected, so that they now encompass the globe. The histories of science fiction and biology are full of stories of pioneers opening new doors—be they doors of greater representation or greater understanding, or both—and others following. If evolution has taught us anything, it’s that nature abhors a monoculture, and the universe tends towards diversification; healthy communities are ones which understand that we are not apart from the world, but of it, and that diversity of types, be they cells or perspectives, is a strength.

Kelly Lagor is a scientist by day and a science fiction writer by night. Her work has appeared at Tor.com and other places, and you can find her tweeting about all kinds of nonsense @klagor

I’m glad to see these essays – they provide a welcome range of perspectives on both biology and SFF.

Verne’s tech-forward adventures and Wells’ sociological allegories established two distinctive styles, but still centered on white imperialism and class struggle.

Centred on, yes, I suppose, but – in both cases – extremely and explicitly critical of it, and centring a non-white perspective.

The hero of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, Captain Nemo, is an Indian, a veteran of the anti-British Great Rebellion of 1857, and a vocal supporter of Indian independence. As for Wells, The War of the Worlds is set in Surrey but it is an explicit allegory for European imperialism in Africa and Australia: the Martians are the Europeans and the English are the locals.

The reality’s the reverse of what you imply – “Subsequent futures depicted in Verne-like pulp and Golden Age stories, where lone white heroes conquered evil powers or alien planets, mirrored colonialist history and the subjugation of non-white races.” That isn’t the kind of story Verne or Wells wrote.

ajay @@@@@ 2:

The hero of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, Captain Nemo, is an Indian, a veteran of the anti-British Great Rebellion of 1857, and a vocal supporter of Indian independence.

I think this was made explicit in the second book (The Mysterious Island); his background in the first book is (mostly) unspecified. Supposedly, the original draft of Twenty Thousand Leagues had Nemo as Polish veteran of the January Uprising (against Russia), but his publisher was afraid that detail that would not make it do well in the Russian market and had Verne remove it.

Interesting! I didn’t know that detail. But the publisher obviously didn’t worry about losing the British market for The Mysterious Island – or else thought they wouldn’t notice (or mind)…

I notice from the text that their origin is kept ambiguous. Nemo talks to his crew in “an unknown tongue. It was a sonorous, harmonious, and flexible dialect, the vowels seeming to admit of very varied accentuation” and Arronax remarks that “the nationality of the two strangers [Nemo and his crewman] is hard to determine. Neither English, French, nor German, that is quite certain. However, I am inclined to think that the commander and his companion were born in low latitudes. There is southern blood in them; but I cannot decide by their appearance whether they are Spaniards, Turks, Arabians, or Indians. As to their language, it is quite incomprehensible.”

ajay @@@@@ 4:

There may or may not have been a political element, in that in the 1870s Russia was an ally of France, while Britain was more of an uneasy rival (despite what happened in the Crimean War).

I’m kind of curious how much “losing the Russian market” meant losing sales of Russian translations versus losing sales of French editions being bought by Francophone Russians, in a time when being able to speak French was a sign of culture among upper-class Russians.